Divergent Ideas: How LEGO Themes Evolve

IMAGE COURTESY OF LEGO VIA JAY’S BRICK BLOG

Like a sleeper agent, I was activated when I was given the words “LEGO updated a visual identity.” Originally, that was all this article was going to be about. For some time, I mulled it over and figured there had to be more to talk about. Follow along for another of my mad ramblings, identifying the greater complexity when a theme beckons for more than was ever intended for it.

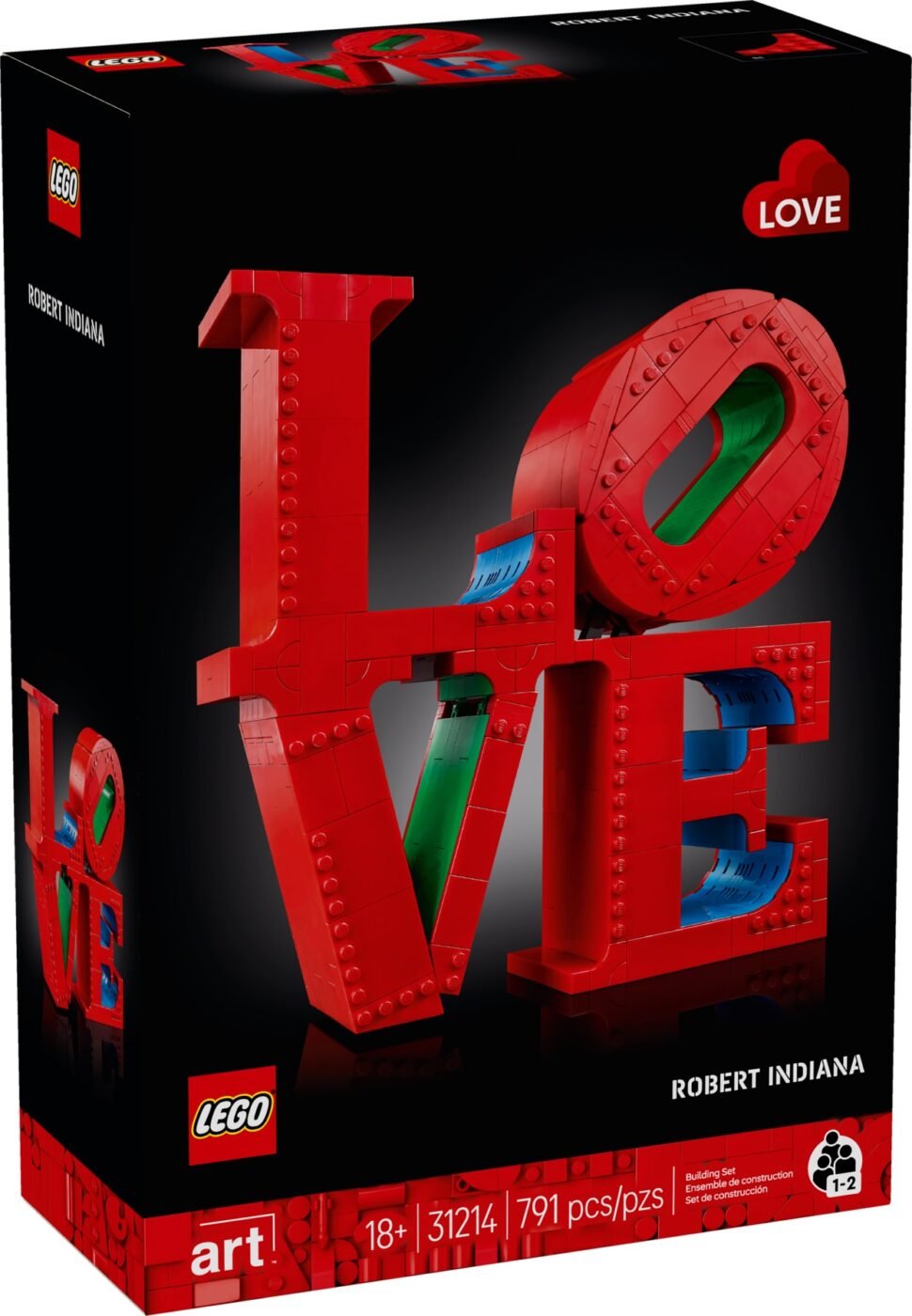

Back in January, LEGO released 31214 LOVE, a beautifully crafted replica of Robert Indiana’s similarly titled 1970 sculpture, based on his 1965 painting, based on his 1964 Christmas card… but that’s a story for another article already brilliantly covered by our very own Dave Schefcik.

What was interesting about this release is that it concreted a new direction in the LEGO Art theme itself. It came with a new theme logo! More on that later, though. How did we get here?

In the Beginning, There Were Dots

You can’t talk about the LEGO Art theme without mentioning LEGO Dots. About five months before the initial release of the Art theme, the controversial Dots theme made its debut. The theme revolved around the use of 1x1 tiles of various colours, shapes and prints, applied to builds and a new wrist-strap element, as an outlet of artistic expression for kids. The Art theme was simply a more mature manifestation of this philosophy.

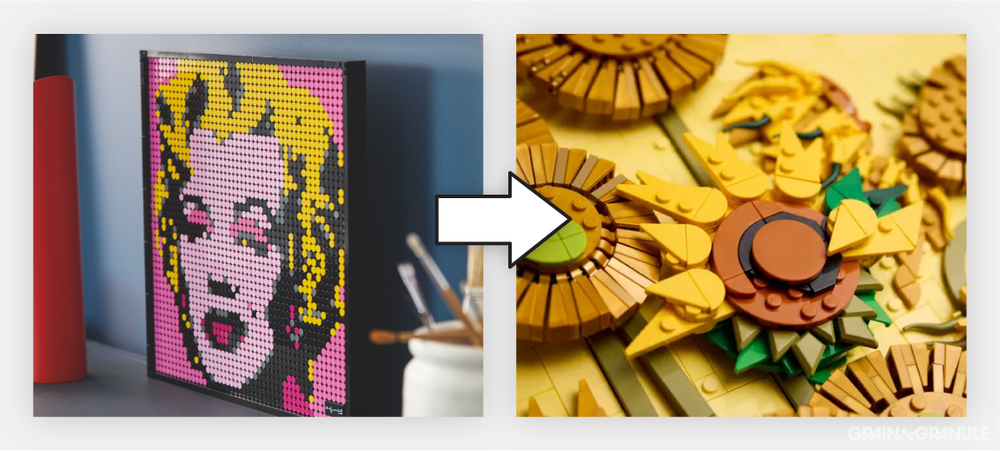

IMAGE COURTESY OF LEGO

LEGO Art started as purely mosaic depictions of various celebrities, characters and IPs, using the same 1x1 round tiles in a huge variety of colours. This is not the first time LEGO had dabbled in the medium before, with promotional sets in 2018, subthemes of both LEGO Sculptures and Creator in 2003 and 2007 respectively, Duplo sets, and the popular Personalised Mosaic Maker installation now in various locations including the Leicester Square LEGO Store. Heck, one of the earliest brick-based sets was a mosaic creation set all the way back in 1955!

Mosaics had been steadily growing in popularity as a personal and collaborative build format in the years prior to the Art theme ever existing. People like the wonderful former Legoland California Master Builder Mariann Asanuma took mosaics to a new level with her studs in all directions building style, looking like old glass tile-work. It was only natural that they explore the possibilities of the medium again, and this time they struck a chord with a much wider audience, given the IP now available to them.

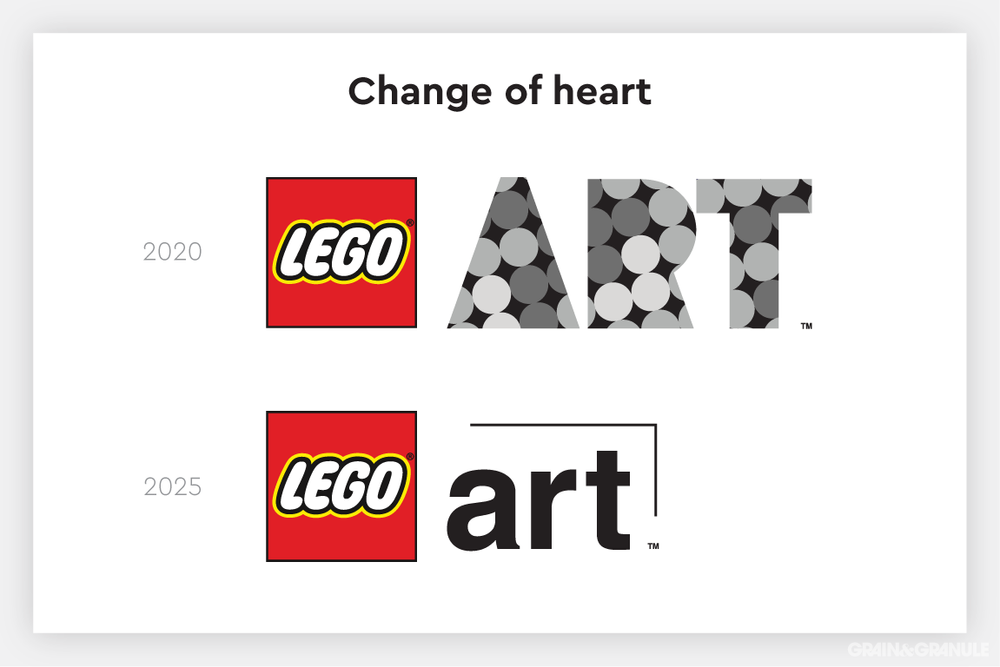

The original LEGO Art logo aptly captured the use of 1x1 round tiles which, to its credit, was right for the time—but as the theme progressed, it made less sense. The series saw more depth, with sculptural pieces like Spiderman and the Rolling Stones, as well as truly mould-breaking concepts like the Modern Art freeform set. It was apparent that this theme could be more, and customers were clearly receptive to that shift.

With that preamble out of the way, the new 2025 visual identity now makes sense. Rolling the box design into the existing 18+ range aesthetic, and updating the theme logo to something that would apply to everything with that ubiquitous Helvetica typesetting that’s home pretty much anywhere it is used. That’s the point. It will in theory work with any form of art under the Art range’s umbrella, as the theme matures and evolves, just like the logo itself has an implied frame.

On the Nature of Creativity (and Business)

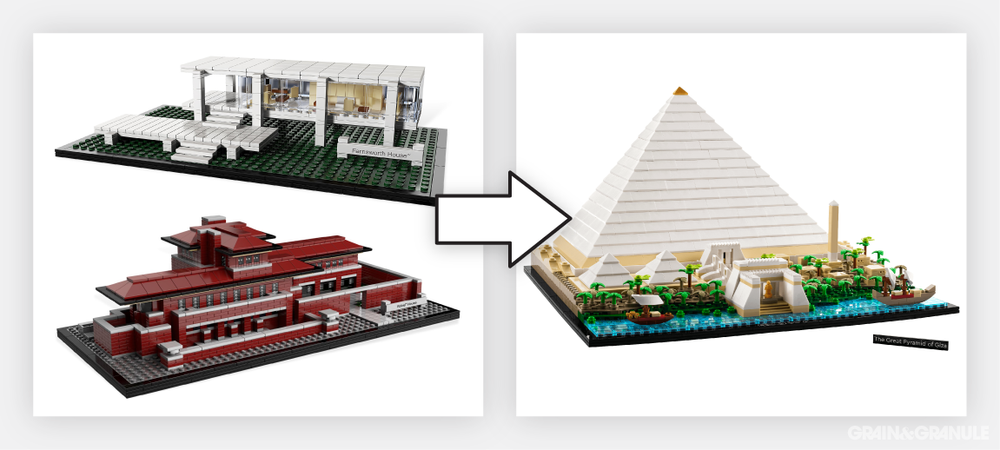

Following the lineage of the Architecture theme has some parallels to how the Art theme developed over time. The evolution of the Architecture theme has been studied in an in-depth article earlier this year, but I can retell the journey in brief.

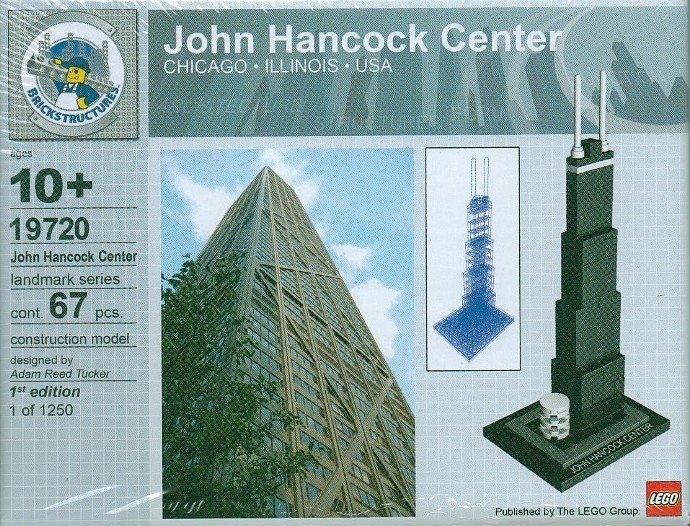

With initials like his, these sorts of builds are only natural. IMAGE COURTESY OF SLATE

IMAGE COURTESY OF BRICKSET

Chicago architect Adam Reed Tucker started building scale replicas of various skyscrapers out of LEGO bricks, and the public resonated with them immediately. The LEGO Group saw potential here, and with their help, Adam released two Chicago-based icons of architecture: Sears Tower and the John Hancock Center, as a limited-run set.

The proof of concept was successful and that same year, we saw the same two sets released officially under the new Architecture banner. These sets were followed up with the Empire State Building and the Seattle Space Needle, two other legendary feats of engineering and striking architectural form.

For some time, more mainstream landmarks were interspersed with works from Architecture greats like Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. That’s not to say that the works from these designers weren’t in the least bit mainstream, which they ostensibly are, but there’s a definite difference in public awareness and passion between the Villa Savoye and something like Big Ben.

And I don’t mean to sound reductionist about this shift. The recent releases like Notre-Dame de Paris and Trevi Fountain are shining examples of the rich textural and structural forms that can be brought to life in brick; it’s the perfect medium for scale modelling. There’s nothing inherently wrong with gradually moving away from niche examples of the study of forms to the more universal experience of reliving fond holiday memories. Architecture is the study and discipline of the use of space and how humans inhabit it, with an emphasis on how it can make us feel. It just so happens that more people feel more things about certain buildings in more prominent locations of historical importance.

Somewhere along the line, especially with the release of the ‘Skylines’ subtheme, we saw an abstraction of that study of form into its most basic principles. Monuments and buildings were represented with only a handful of parts and still convey meaning. That is, in essence, the original intent of the theme. This move to more obvious, well-known structures is simply a matter of market broadening and demand.

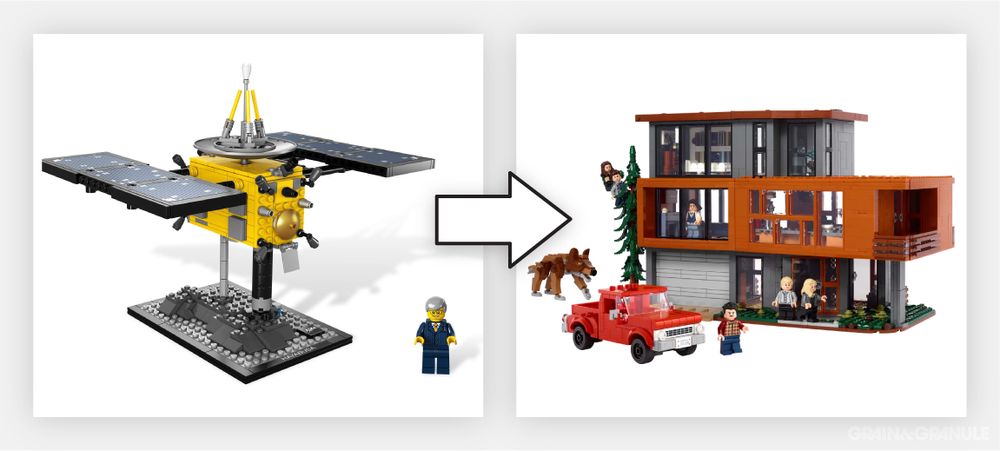

A similar evolution can be viewed again for LEGO Ideas, formerly LEGO Cuusoo. What started as a way for topics and entities that may never get the brick treatment to have a platform to help make that happen, has become a place for people to share their ideas for how their favourite shows, characters and concepts could be transformed into plastic. Again, this is at no discredit to the modern Ideas sets, but can you imagine the uproar if a Japanese Research Submersible from 1991 came out ahead of fifty other voted submissions? That could only have happened with the smaller, more specific audience that Cuusoo initially had in Japan.

As the site and user-base grew, so did LEGO’s power with licensing arrangements. The platform has always had the same ability, but it now manifests that ability to a much wider demographic. What LEGO Ideas allows the company to do is keep their finger on the pulse for some slightly more obscure topics where customer interest may lie.

There have been other paradigm shifts in LEGO themes before. Technic going from simple mechanical principles to more complex mechanical principles with the added challenge of aesthetic rigour and brand deals is just another example of this evolution. Ninjago banking on its play features when what the audience really wanted was a story. The ‘for girls’ themes all trying desperately to understand their customers motivations and Friends finally understanding that it could also be more than just play-sets, doll houses and jewelry with a bit more authenticity.

All of these themes start with a concept, and that concept remains, sometimes just hidden under a few layers of corporate considerations. And contending with more customers who have more motivations and opinions that need catering, too. That doesn’t at all diminish the importance of that underlying concept.

Always Has Been

This increase in build complexity, market acuity, and market involvement is a dynamic, living process. The company of course wants more customers, so they focus on concepts that net the widest audiences. It’s no coincidence that the Chinese New Year sets had a bold new approach from 2018, around the same time that The LEGO Group won a huge copyright case in China against counterfeiters.

The audience gets bored with the same kinds of sets so the company answers with fresh ideas, new licences, and new parts. The fan community finds new techniques using the new parts, and the company can use some of those techniques to increase the quality and interest of the building experience. Think of the number of AFOLs that have gone on to become LEGO designers. It is all cyclical.

None of this process exists in a vacuum. Every set you purchase, friend you convince, post you make online, RLFM blog you interact with and support on Patreon, all have a small part in shaping the potential endless possibilities of the brand and, in turn, the brick. That’s something we can all love.

Where else have you seen a theme take on a new approach? Let us know in the comments below!

Do you want to help BrickNerd continue publishing articles like this one? Become a top patron like Marc & Liz Puleo, Paige Mueller, Rob Klingberg from Brickstuff, John & Joshua Hanlon from Beyond the Brick, Megan Lum, Andy Price, Lukas Kurth from StoneWars, Wayne Tyler, Dan Church, and Roxanne Baxter to show your support, get early access, exclusive swag and more.